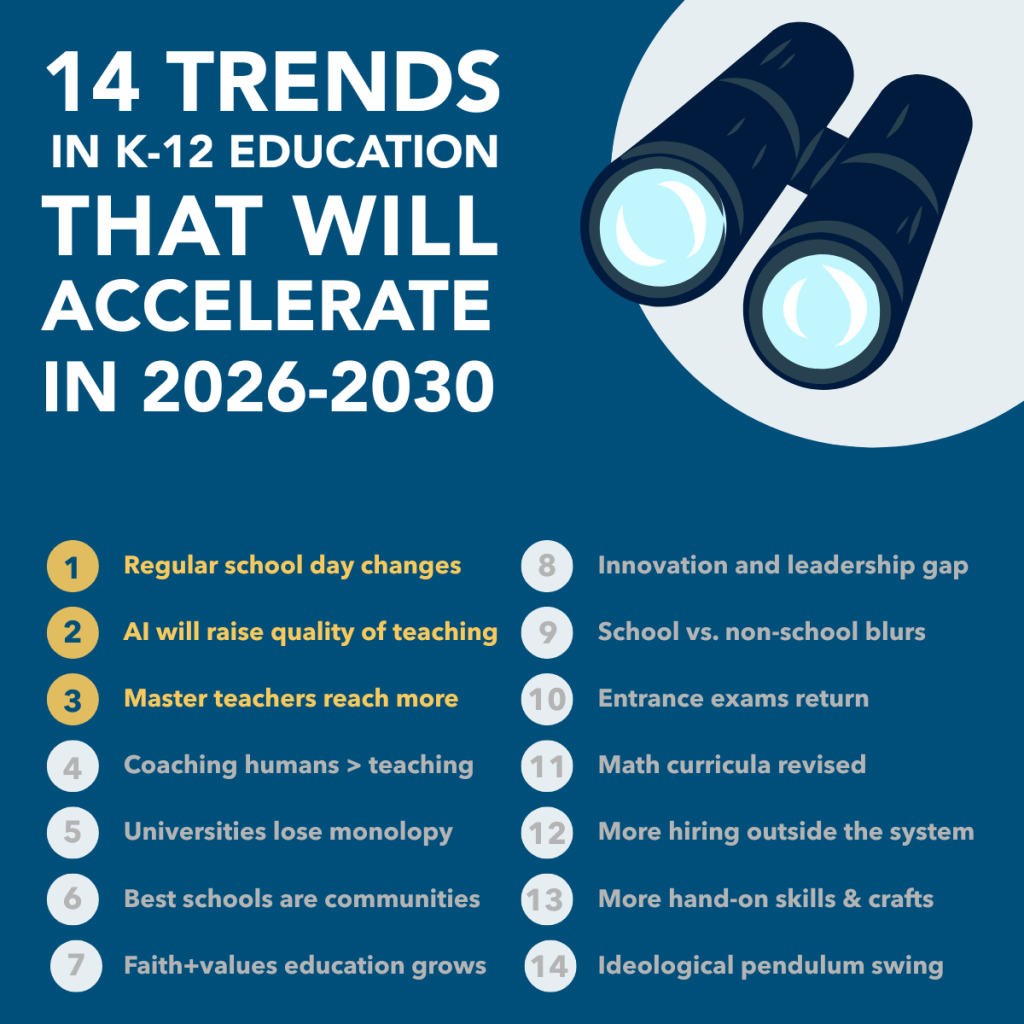

14 Trends in K-12 Education that will accelerate in 2026-2023

The article previous to this one provides a global overview of the trends that are poised to accelerate and significantly change K-12 education in the next 5 years. I explained there that the point of this discussion is to alert boards and policy makers and to prepare strategically for what might be on the horizon for one of our civilization’s most important industries. The changes will be gradual, then sudden. And as Suleyman argues in his latest work The Coming Wave, we educated people have a tendency to downplay or reject narratives or possible futures that we don’t like or don’t want to contemplate until they overwhelm us. Trends #1-3 are explained below. These three seem obvious to accelerate because they’re already well underway.

#1. The regular school day will be more flexible or disappear in some schools.

Any home school or online school parent will tell you they get as much learning done in half a day as most schools do in a full day.

With too many students and too few classrooms in many districts, and with physical buildings among the most expensive components of education, it just makes sense that more and more schools – especially high schools – will develop more agile schedules that spread the school day over a longer period. Populations fluctuate, and yet we still build single-use multi-million dollar buildings far bigger and less flexible than they should be.

Staggered or extended school days are an efficient and sensical solution allowing many more students to use a single building and potentially creating stronger community connection within smaller cohorts. The highest performing schools throughout North America have cohorts of roughly 75-125 students per grade which is small enough to intentionally create community, but large enough to provide quality programs.

At a time when schools are facing an unprecedented mental-health and anxiety crisis, packing 1,500 or 2,000 or more adolescents into a single building at the same time is clearly not the optimal environment for learning or flourishing. Smaller cohorts moving through a shared space at different times can reduce sensory overload, improve adult-student connections, and create calmer, more-appropriately scaled learning communities. Done well, this can strengthen relationships, improve supervision, and foster a greater sense of belonging.

There’s also value in a schedule that allows more time to work part-time jobs or gain valuable experience through volunteering, shadowing mentors or apprenticing in the community. Making more room in the day for these experiences builds maturity, responsibility, and real-world competence missing from a typical school day.

Growth in many districts, independent schools and even online schools is outpacing available space, capital costs continue to rise, and the rhythms of family and work life no longer resemble the mid-20th-century model on which the school day was built. Requiring all students to go to school Monday to Friday, 8:30 to 2:30 or 3:00 just doesn’t make sense. Today’s families are navigating shift work, hybrid roles, and non-standard hours that no longer align neatly with an 8:30–3:00 school schedule.

AI-enabled hybrid learning and tutoring will rapidly accelerate in the next five years, and flexible scheduling will allow more students to access the same buildings across longer, staggered days, reducing construction pressure while increasing personalization and access.

In many districts, the problem is not a lack of students but a lack of classrooms. Recent school projects cost the public $800-$1200 per square foot. Physical buildings are among the most expensive inputs in education, and building new schools is often slower and costlier than demand allows. As a result, it is both logical and inevitable that more schools (particularly at the secondary level) will move toward more agile scheduling models. There’s already many school districts, including Surrey Schools – Canada’s largest district, moving in this direction and it will only accelerate in the next five years.

#2. AI will raise the bar of teaching quality.

Almost 20 years ago, Harvard professor Clayton Christensen got it wrong. Christensen applied his theory of disruptive innovation to schools and predicted that computers would revolutionize K-12 education. In 2026 there’s no shortage of data that proves computers simply made education worse for most learners, and it made it far more expensive for tax payers. Notably, education cultures like those found in Singapore, Korea or Japan, who have far higher achievement scores in disciplines like science and mathematics when compared to Canada, have noticeably far less computers and laptops in the hands of students in general classrooms. Personal computers did not revolutionize education, and now these devices are likely contributing to a myriad of other health-related problems in youth.

What Christensen got right is that for a technology to revolutionize a sector of the economy it doesn’t have to be great, it just has to be “good enough” and cheap enough to replace what is currently in use. This is what General Artificial Intelligence will do in K-12 teaching. AI will never match the quality of a master teacher, skilled in both building rapport and relationship, as well as his subject matter, but it doesn’t have to be. It only has to be better than the average teacher, which it likely is already in many key areas of teacher work: assessment, lesson planning, course overviews and report writing. Tasks that took days, weeks or months five years ago, like writing a course syllabus for English 8, can be done now in minutes. There’s no reason now for any student to need to wait more than 24 hours for feedback on an assignment, and for many tasks, the feedback should be timely and immediate, which is something that would exponentially improve teacher quality overnight.

Similarly, the time teachers currently spend hours on, with very little juice for the squeeze, such as report card writing, can be completed in a fraction of the time. Collection of data on student achievement will increasingly be more frequent as more schools adopt programs like Amira Learning – and these types of programs will only improve between now and 2030. In BC, the adoption of the Continuous School Improvement framework (or in other jurisdictions where there are similar regimes in place) will increasing make student achievement and wellness data more transparent, replacing the almost absurd emphasis that some parents place on FSA exams as a marker of school quality.

Instead, data on what students are learning and which ones are not will also make it more transparent which teachers are impacting student learning and which ones are not. We already know there’s a “narcissism of small differences” between one school and the next school within the same community, but AI will make the often massive differences between teachers in the same school very transparent as policy makers and stakeholders in education will have immediate and powerful data analysis to gauge a teacher’s impact on their students’ achievement.

In short, many of the things that teachers have spent massive amounts of time working on, but which also cause massive variability in teacher quality, will be standardized and levelled. Poorly organized, less thoughtful and less creative teachers will be raised to higher levels of competence with more time for student relationship building. Teachers who struggle to provide meaningful feedback to improve a student’s performance, will have new tools available to bring them closer to mastery. It may not be ideal in this imagined future as it will fall short of experiencing a highly competent teacher in front of every student, but it will be better and more reliable than what is the norm today.

#3. Master teachers will reach more students

In my 26+ years in education, the call for more funding, to hire more teachers, to build more classrooms and provide more resources has never ceased. I’ve adapted, and so have most successful school leaders. There is no magic pool of people out there who will suddenly appear and take jobs in teaching if only we got the compensation and working conditions right. We have to think more creatively.

What we do know is that there are thousands of highly skilled, wonderfully creative, resourceful teachers who make magic happen in their classrooms. AI is already helping many of these teachers be more effective, more efficient and more creative. Yet, our structures limit their access to the same number of students, and the same compensation as less energetic, lower capacity educators. Persistent teacher shortages are accelerating models that will disrupt ratios of teachers to students. Highly effective teachers can reach more students through hybrid delivery, recorded instruction, team-based teaching, and AI-supported facilitation. This reshapes staffing by pairing skilled teachers with facilitators, mentors, and learning coaches rather than relying solely on one-teacher-one-classroom structures.

We predict that by 2030 there will a global need of somewhere in the ballpark of 44 million K-12 teachers. We’re an estimated 20 million too-few teachers today. There’s no government policy or funding solution to this problem, and if there was, we would only be stealing human resources from another, less resourced part of the globe. One solution to this problem is well-underway in Canada and the United States as thousands of fewer families choose K-12 community-based schools for their child’s education and are flocking to online, hybrid and home school options. The explosion has been massive.

Another potential solution to this problem is to simply make it easier for highly skilled teachers to reach more students. This is inevitable, and will only be prevented in districts and regions where school boards and collective agreements are not agile enough to adapt to the rapidly changing educational landscape. If they don’t adapt, they’ll have even more problems recruiting and retaining the most competent teachers.

If lesson planning, assessment, feedback and course design are assisted by AI, and if school days and schedules are more flexible, there is no reason why good teachers – especially at upper grades – can’t reach and teach more students. This is an easy win-win for everyone, and if compensation structures are adjusted teachers can earn beyond the standard 1.0 FTE. Some teachers are already doing this, albeit discretely, as hundreds already work as full-time or part-time teachers in brick-and-mortar schools, but also work for online schools often doing both simultaneously.